A parameter

with a const is different from one without const in terms of a function

signature. But is that actually true? Is A(x: T) really different from B(const x: T)?

Disclaimer:

In this article I am focusing on the default calling convention on Windows in

Delphi which is register.

We will go onto

a journey through some assembler code and look into various method calls with different

typed parameters both const and no const and explore their differences. Don’t

worry - I will explain the assembler in detail.

I have following

code for you that we will use with different types to explore:

{$APPTYPE CONSOLE}

{$O+,W-}

type

TTestType = …;

procedure C(z: TTestType);

begin

end;

procedure A(y: TTestType);

begin

C(y);

end;

procedure B(const y: TTestType);

begin

C(y);

end;

procedure Main;

var

x: TTestType;

begin

A(x);

B(x);

end;

We will put

different types for TTestType, put a breakpoint into Main and see how the code

looks like for the calls and inside of A and B. I will be using 10.4.2 for this

experiment. We will ignore the warning because it does not matter for the

experiment.

Let’s start

with something simple: Integer

When we

look into the disassembly we see the following:

Hamlet.dpr.24: A(x);

00408FA9 8BC3 mov eax,ebx

00408FAB E8E8FFFFFF call A

Hamlet.dpr.25: B(x);

00408FB0 8BC3 mov eax,ebx

00408FB2 E8E9FFFFFF call B

eax is the

register being used for the first and only parameter we have in our routines. ebx

is the register where x is being stored during the execution of Main. No difference

between the two calls though – and here is how it looks inside of A and B. In case

you wonder – the calls to C are just there to prevent the compiler to optimize away

some code which will be important later.

Hamlet.dpr.12: C(y);

00408F98 E8F7FFFFFF call C

Hamlet.dpr.13: end;

00408F9D C3 ret

Hamlet.dpr.17: C(y);

00408FA0 E8EFFFFFFF call C

Hamlet.dpr.18: end;

00408FA5 C3 ret

Also the

same, the value is being kept in the register it was being passed in – eax –

and C is called. We get the same identical code for various other ordinal types

such as Byte, SmallInt or Cardinal, enums or sets that are up to 4 byte in size,

Pointer or TObject (did someone say “not on ARC”? Well we are on 10.4.2 – I erased

that from my memory already – and soon from my code as well).

Let’s

explore Int64 next:

Hamlet.dpr.24: A(x);

00408FC7 FF742404 push dword ptr [esp+$04]

00408FCB FF742404 push dword ptr [esp+$04]

00408FCF E8C8FFFFFF call A

Hamlet.dpr.25: B(x);

00408FD4 FF742404 push dword ptr [esp+$04]

00408FD8 FF742404 push dword ptr [esp+$04]

00408FDC E8CFFFFFFF call B

And B and C:

Hamlet.dpr.11: begin

00408F9C 55 push ebp

00408F9D 8BEC mov ebp,esp

Hamlet.dpr.12: C(y);

00408F9F FF750C push dword ptr [ebp+$0c]

00408FA2 FF7508 push dword ptr [ebp+$08]

00408FA5 E8EAFFFFFF call C

Hamlet.dpr.13: end;

00408FAA 5D pop ebp

00408FAB C20800 ret $0008

Hamlet.dpr.16: begin

00408FB0 55 push ebp

00408FB1 8BEC mov ebp,esp

Hamlet.dpr.17: C(y);

00408FB3 FF750C push dword ptr [ebp+$0c]

00408FB6 FF7508 push dword ptr [ebp+$08]

00408FB9 E8D6FFFFFF call C

Hamlet.dpr.18: end;

00408FBE 5D pop ebp

00408FBF C20800 ret $0008

On 32bit an

Int64 is passed on the stack as you can see – nothing fancy here but reserving

a stack frame and passing on the value to C. But no difference between the two

routines.

I don’t

want to bore you death with walls of identical assembler code so I can tell you

that for all the floating point types, enums and sets regardless their size the

calls to A and B are always identical.

But now for

the first difference – lets take a look at set of Byte – the biggest possible

set you can have in Delphi. A set is actually a bitmask with one bit for every

possible value – in this case this type is 256 bit in size or 32 byte. Like many

other types that don’t fit into a register it will actually be passed by reference

– this time I also show you the prologue of Main where you can see that the compiler

reserved 32 byte on the stack for our x variable and that this time the address

of the value is being passed to A and B which is in the esp register - the

stack pointer:

Hamlet.dpr.23: begin

00408FC8 83C4E0 add esp,-$20

Hamlet.dpr.24: A(x);

00408FCB 8BC4 mov eax,esp

00408FCD E8C6FFFFFF call A

Hamlet.dpr.25: B(x);

00408FD2 8BC4 mov eax,esp

00408FD4 E8DFFFFFFF call B

Let’s take

a look into A where we can see the first difference:

Hamlet.dpr.11: begin

00408F98 56 push esi

00408F99 57 push edi

00408F9A 83C4E0 add esp,-$20

00408F9D 8BF0 mov esi,eax

00408F9F 8D3C24 lea edi,[esp]

00408FA2 B908000000 mov ecx,$00000008

00408FA7 F3A5 rep movsd

Hamlet.dpr.12: C(y);

00408FA9 8BC4 mov eax,esp

00408FAB E8E4FFFFFF call C

Hamlet.dpr.13: end;

00408FB0 83C420 add esp,$20

00408FB3 5F pop edi

00408FB4 5E pop esi

00408FB5 C3 ret

First the

non-volatile registers (that means their values need to be preserved over subroutine

calls, in other words, when A returns the values in those registers must be the

same as they were before A was being called) are being saved. Then we see again

reserving 32byte on the stack as previously.

The next

four instructions: the parameter being passed eax is stored in esi, that is the

address to our value x that we passed in y, then the address of esp is loaded

into edi. The rep instruction does something interesting: it repeats the movsd

instruction (not to be confused with the movsd – hey it’s called complex

instruction set for a reason) –moving 4 byte as often as ecx says using esi as

source address and edi as destination. Long story short, it does a local copy

of our set.

There we

have our first difference – the compiler produces a copy of our parameter value

– if the C call would not be here the compiler would actually optimize that

away as it detects there is nothing to do with y. And it does so even though we

just read the value and not actually modify it as we could with a non const

parameter.

Finally the

type many of you have been waiting for: string

Hamlet.dpr.24: A(x);

004F088B 8B45FC mov eax,[ebp-$04]

004F088E E88DFFFFFF call A

Hamlet.dpr.25: B(x);

004F0893 8B45FC mov eax,[ebp-$04]

004F0896 E8CDFFFFFF call B

Since string

is a managed type – meaning the compiler inserts code that ensures its initialized

as empty string and gets finalized we got quite some code in Main this time and

the variable is on the stack – string is a reference type so in terms of size

its just the same as a pointer fitting in eax. Just to avoid confusion – string

is a reference type but the parameter is by value – the value of the string

reference is passed in the eax register just like earlier for Integer and alike.

Fasten your

seatbelts as we take a look into the code of A:

Hamlet.dpr.11: begin

004F0820 55 push ebp

004F0821 8BEC mov ebp,esp

004F0823 51 push ecx

004F0824 8945FC mov [ebp-$04],eax

004F0827 8B45FC mov eax,[ebp-$04]

004F082A E8D994F1FF call @UStrAddRef

004F082F 33C0 xor eax,eax

004F0831 55 push ebp

004F0832 685D084F00 push $004f085d

004F0837 64FF30 push dword ptr fs:[eax]

004F083A 648920 mov fs:[eax],esp

Hamlet.dpr.12: C(y);

004F083D 8B45FC mov eax,[ebp-$04]

004F0840 E8AFFFFFFF call C

Hamlet.dpr.13: end;

004F0845 33C0 xor eax,eax

004F0847 5A pop edx

004F0848 59 pop ecx

004F0849 59 pop ecx

004F084A 648910 mov fs:[eax],edx

004F084D 6864084F00 push $004f0864

004F0852 8D45FC lea eax,[ebp-$04]

004F0855 E8CA93F1FF call @UStrClr

004F085A 58 pop eax

004F085B FFE0 jmp eax

004F085D E9DA89F1FF jmp @HandleFinally

004F0862 EBEE jmp $004f0852

004F0864 59 pop ecx

004F0865 5D pop ebp

004F0866 C3 ret

Ok, that’s

quite a lot of code but the important thing is this - the compiler basically

turned the code into this:

var

z: Pointer;

begin

z := Pointer(y);

System._UStrAddRef(z);

try

C(z);

finally

System._UStrClr(z);

end;

end;

The System

routine _UStrAddRef checks if the string is not empty and increases its reference

count if it’s not a reference to a constant string because they have a reference

count of -1 meaning they are not allocated on the heap but point to some

location in your binary where the string constant is located. _UStrClr clears

the passed string variable and reduces its reference count under the same

conditions.

So why is

that being done? The string was passed as non const causing the compiler to ensure

that nothing goes wrong with the string by bumping its reference count for the

time of the execution of this routine. If some code would actually modify the

string the code to do that would see that the string – assuming we have one

that had a reference count of at least 1 when entering the method – has a

reference count of at least 2. This would trigger the copy on write mechanic

and keep the string that was originally passed to the routine intact because

even though a string is a reference type underneath it also has characteristics

of a value type meaning that when we modify it we don’t affect anyone else that

also holds a reference.

Now the code of B:

Hamlet.dpr.17: C(y);

004F0868 E887FFFFFF call C

Hamlet.dpr.18: end;

004F086D C3 ret

That’s almost

disappointing after so much code in A. But joking aside the const had a significant

effect: all that reference bumping, try finally to ensure proper reference

dropping in case of an exception is not necessary because the parameter being

const ensures that it cannot be modified.

The code being

executed in A is not the end of the world or will utterly destroy the performance

of your application but is completely unnecessary most of the time. And in many cases it can indeed mean the difference for the fast execution of an algorithm. Yes, I know

we can construct some terrible code that causes bugs when the parameter is

const because we have a circular data dependency but let’s not talk about this –

because this

has already been discussed.

Similar code

can be found for interfaces, dynamic arrays and managed records (both kinds,

records with managed field types and the new custom managed records).

There are not

many more types left – records and static arrays depending on their size are either

passed by value or reference or in the fancy case of being of size 3 pushed onto

the stack.

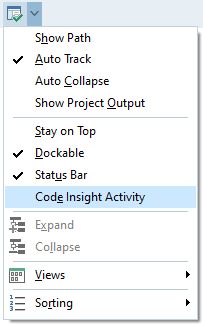

For a complete summary please refer to this table.

As we can see from the caller side a const and a non const parameter are not any

different for the register calling convention. For other calling conventions

however they differ – especially on non Windows platforms. As an example with

the stdcall convention a record that is bigger than a pointer is being pushed

onto the stack as a non const parameter while as a const parameter just its

address is being pushed so basically passed by reference.

That was a rather lengthy adventure – but what did we learn?

For most code on Windows a const parameter is actually an implementation

detail and does not affect the code on the caller side. But knowing that it depends on the platform

and the calling convention makes it clear that as much as some would like non

const and const parameters to be compatible in order to easily add some missing

const throughout the RTL or VCL where it would have a benefit of removing unnecessary

instructions is simply impossible. Nor could we simply assume non const

parameters to behave similar to const parameters.

Using const parameters can avoid unnecessary instructions and speed up your code without any cost or side effects. There is no reason to not make your string, interface, dynamic array or record parameters const. That can be even more important if you are a library developer.

In the next

article we will explore another kind of parameter: out